[Note: This is a re-post from last year. I’ve made some minor alterations to the text, but the content is mostly the same.]

Voice is the second most important aspect of rhetorical (or persuasive) communication. When the communication is written, we call this aspect the author’s “style.” I assume that many of you have been introduced to the style analysis paper in other courses, probably Freshman or Sophomore English. If not, have no fear. Here is a quick review.

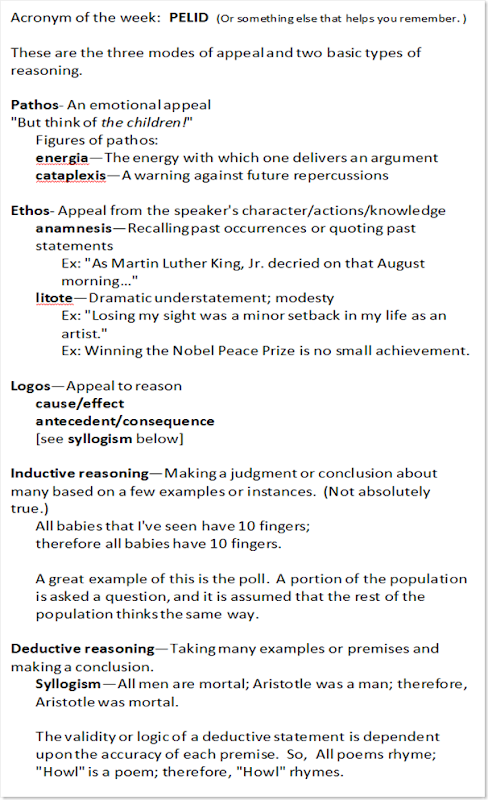

When we describe voice in a rhetorical argument, we are actually describing six things. I will refer to them using the acronym T-DIDLS (“tee-diddles”) because it sounds funny and we can all remember it. The first letter stands for TONE, which will be described throughout this series. The second is DICTION, which we will be covering today.

Diction is how we describe an author’s choice of words. You will rarely find a character in a novel “saying” anything; often, they “shout,” “mutter,” “respond,” or “sneer.” This allows the author to pack as much meaning into one word as possible. The same goes with descriptive words. So, instead of describing a scene like this:

The old cat was bad for the man’s asthma.

An author could describe it this way, with more interesting diction:

The dandered and decrepit cat irritated her owner’s asthma.

Okay, so I may not be the next Faulkner, but I hope you get the idea. The words “dandered” and “decrepit” in the second sentence replace “old” in the previous sentence. Not only is the second sentence more interesting, but it more specifically describes the situation. By adding the word “irritated,” a TONE of frustration or annoyance is added to an otherwise frank explanation of events.

Another aspect of diction depends on the author’s purpose. If the author intends to entertain, there will be much laughter and gaiety all around. His or her word choice will reflect a relaxed diction; informal and colloquial words like “um,” “okay,” “well,” and “K,” “LOL,” “whatcha up to?,” and “nuthin'” are all relaxed words that put the reader in a mind to be entertained. On the other hand, if the author’s purpose is to inform, then the words will be much more formal. Academic writing, presentations, most speeches, and any proposals or resumes are written in precise and proper words:

Both Vladimir Nabokov and Marcel Proust state that the worldview they held as children was slanted and inaccurate, yet each devotes much of his story to the recollection of his formative years. Each has devoted numerous pages to narrating or explaining scenes of his early youth that have affected him later in some manner, profound or otherwise. One should certainly wonder, then, what it is about childhood memories that endow them, for these men, with such weight in later life?

Enough of that. It informs, but only if you are really interested in Speak, Memory or Remembrances of Things Past. Which we aren’t; not at this point.

Quick Self-Quiz: Can anyone label the diction I am using throughout this explanation? Take into consideration my purpose and goals.

[This post was WinsomeWiki’d on 5 Jul. 2009.]