Been an amazing week so far: great discussions, solid journals, impressive insights. Very excited for this year.

Tuesday and Wednesday were devoted primarily to journal checks. While you are all used to annotations and journaling, the scope of this paper is greater than you’ve likely encountered. I cannot emphasize enough how important it is for you to continue asking questions, seeking answers, trying out connections, and writing down those quotations. The grades are in the grade book. Remember, your current scores are based on a 5-point scale and we’re going for perfection; if you have a 3 in vocab, make sure you’re writing down (and defining!) unfamiliar words. If you were writing down quotations without making connections, make them and your grade will go up.

We’ve continued our discussion of the Romantic Era and its reflection in this novel. Look back for other links about this period, but I’ll recommend this site again. Worth a look—really.

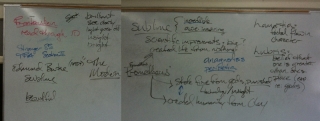

We discussed the romantics’ infatuation with two unlikely heroes: Milton’s Satan and Prometheus. Both challenged the gods and were punished for it, much like our poor cocky hubristic protagonist. We spent most of the hour making connections between Enlightenment/Romantic ideas about the sublime and beautiful and Victor’s reaction to his creation:

I had desired it with an ardour that far exceeded moderation; but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart. Unable to endure the aspect of the being I had created, I rushed out of the room, and continued a long time traversing my bedchamber, unable to compose my mind to sleep.

I also told the relevant stories of Prometheus ((Though I left out the Pandora bit—gotta have a cliffhanger, don’t I?)), but here is a great resource for further research.

Our discussions resulted in the following, which may only be clear for those who were present for the discussion. ((And my ham-fisted Paint skills coupled with awkward camera angles aren’t helping)) If you weren’t, ask a peer to walk you through it.

We read Goethe’s “Prometheus” (1772–4) and Byron’s… “Prometheus” (1816) in class today, as well. We’ll discuss these tomorrow with Percy Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound (1820), just to drive the point about their obsession home.